Translational Perioperative and Pain Medicine (ISSN: 2330-4871)

ARTICLE DOI: 10.31480/2330-4871/208

Review Article | Volume 12 | Issue 1 Open Access

Anesthesia-Induced Fatigue Spectrum (AIFS) in Perioperative Care (Part 1): Evidence Synthesis and Conceptual Framework

Qin Yin1#, Ming-Yue Cheng1#, Shu Wang2, Yu-E Sun3, Jin-Feng Wang4* and Wei Cheng5*

1The Affiliated Hospital of Xuzhou Medical University, PR China

2Yancheng Third People's Hospital, Yancheng, PR China

3Drum Tower Hospital Affiliated to Nanjing University Medical College, PR China

4The Suzhou Hospital of the Chinese Academy of Traditional Chinese Medicine - Xiyuan Hospital, PR China

5The Affiliated Huai'an No.1 People's Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, PR China

Wei Cheng, MD, The Affiliated Huai'an No.1 People's Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Huai'an 223300, China, Tel: +8618796205791;Jin-Feng Wang, MD, The Suzhou Hospital of the Chinese Academy of Traditional Chinese Medicine - Xiyuan Hospital, PR China, Tel: +8618168779112

Editor: Renyu Liu, MD; PhD; Professor, Department of Anesthesiology and Critical Care, Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, Center of Penn Global Health Scholar, 336 John Morgan building, 3620 Hamilton Walk, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA, Fax: 2153495078, E-mail: RenYu.Liu@pennmedicine.upenn.edu

Received: Sep 16, 2025 | Accepted: Nov 11, 2025 | Published: Nov 15, 2025

Citation: Qin Yin, Ming-Yue Cheng, Shu Wang, et al. Anesthesia-Induced Fatigue Spectrum (AIFS) in Perioperative Care (Part 1): Evidence Synthesis and Conceptual Framework. Transl Perioper Pain Med 2025;12(2):777-787

Abstract

Perioperative research is shifting from “hard” outcomes toward patient-centered endpoints that reflect experience and functional recovery. Postoperative fatigue (POF) directly affects energy, motivation, and activity tolerance yet is often treated as a sub domain within global recovery scales, limiting cross-study comparability. We define the Anesthesia-Induced Fatigue Spectrum (AIFS) as classifiable, quantifiable, and actionable fatigue phenotypes that arise when anesthesia-related exposures (induction/maintenance drugs, opioid-sparing strategies, temperature and circadian management, sedation, regional techniques) interact with inflammatory-metabolic pathways, neural circuits, sleep/circadian biology, and mood. AIFS elevates fatigue to a primary/co-primary endpoint and standardizes assessment windows (baseline ≤ 7 days pre-op; POD 1/3/7/30; optional POD 90) with parallel readouts-PROMIS®-Fatigue (T-scores) and QoR-15-plus digital phenotypes (steps/activity intensity, nocturnal sleep efficiency (SEI) / arousal index (AI), heart-rate variability). Quantified impacts (selected): dexamethasone for PONV prophylaxis shows pooled risks of ≈ RR 0.57 for nausea (95% CI 0.45-0.72) and ≈ RR 0.56 for vomiting (95% CI 0.43-0.72); for maintenance strategy, TIVA vs. volatile typically yields QoR-15 differences within 1 MCID (~6 points) at 24-48 h, attenuating by ~72 h; for subjective postoperative sleep, melatonin shows a small-to-moderate benefit (SMD ≈ -0.30, 95% CI -0.47 to -0.14) and is not recommended for routine use. Actionable fatigue phenotypes are operationalized as decision-relevant patterns (e.g., “bedbound on POD1” vs. “ambulatory but exhausted”). Implementation emphasizes risk-stratified antiemesis with predefined rescue, opioid-sparing within multimodal analgesia, and circadian-friendly nursing (noise/light reduction, protected sleep, temperature management), alongside prespecified models, covariates (pain/sleep/mood), and interval-estimate reporting to enable multicentre synthesis.

A companion paper (Part 2) will detail implementation and quality-improvement operations, standardized windows (72 h/7 d/30 d), parallel PROMIS-Fatigue/QoR-15 with digital phenotypes, and the AIFS-Bundle deployment and governance pathway.

Keywords

Postoperative fatigue, Anesthesia-induced fatigue spectrum, PROMIS-fatigue, Digital phenotypes, Sleep

Introduction

Perioperative research is increasingly shifting from “hard” outcomes (complications, length of stay) toward patient-centred endpoints that better reflect experience and functional recovery [1,2]. Postoperative fatigue (POF) directly affects energy, motivation, and activity tolerance yet is often treated as a subdomain within global recovery scales-diluting effects and limiting cross-study comparability. The PROMIS-Fatigue T-score offers cross-disease, cross-setting comparability, while the Quality of Recovery-15 (QoR-15) captures global recovery and comfort; using them in parallel reduces single-endpoint interpretive bias and facilitates multicentre evidence synthesis [1,3,4]. Early postoperative objective activity (e.g., time ambulating/activity intensity) measured by wearables has been associated with fewer complications and shorter hospital stay, whereas associations with longer-term endpoints (e.g., 30-day readmission) remain uncertain and warrant further validation [2,5].

Current research on POF falls short in three areas: 1) Endpoint selection-fatigue is seldom a primary/co-primary endpoint and is often buried within global recovery scales; 2) Time windows-assessments cluster within the first 24-48 h, with insufficient attention to trajectories between POD 7-30; 3) Measurement integration-patient-reported outcomes and objective digital phenotypes (wearable-derived activity/sleep) are frequently collected in isolation. Our framework addresses these gaps by specifying parallel use of PROMIS-Fatigue and QoR-15 together with early objective activity, consistent with StEP-2025 guidance on standardized endpoints and reporting [1,3-5].

Perioperative systemic inflammation can signal to the brain via humoral routes and vagal afferents, triggering microglial activation and sickness-behaviour-like features (sleepiness, reduced motivation, heightened fatigue) that contribute to next-day fatigue [6-10]. Alterations in the tryptophan-kynurenine pathway-including shifts in key metabolite ratios-relate to effort-reward appraisal and subjective fatigue [7]. Wake pressure and energetic stress elevate adenosine, which modulates cortical excitability via A1/A2A receptors, influencing the arousal-fatigue balance [8]. Sleep and circadian disruption often amplify these phenotypes (phase shifting and stage fragmentation), and a contemporary meta-analysis indicates that melatonin confers only limited benefit for postoperative subjective sleep-routine use is not supported [10].

The Anesthesia-Induced Fatigue Spectrum (AIFS) standardizes terminology and time windows, links exposures to mechanisms and phenotypes, and elevates fatigue to a primary/co-primary endpoint within routine quality governance [1,3-5,10].

Scope note: This methods-first framework defines AIFS and its standardized windows; it does not present new validation datasets, context-stratified effect sizes, predictive modelling, or formal quality indicators.

Concept of Anesthesia-Induced Fatigue Spectrum

The Anesthesia-Induced Fatigue Spectrum (AIFS) denotes recognizable fatigue phenotypes and trajectories that emerge when anesthesia-related exposures (induction/maintenance drugs, opioid-sparing strategies, temperature and circadian management, sedation, regional techniques) interact with inflammatory-metabolic pathways, neural circuits, sleep/circadian biology, and mood. AIFS aims to elevate fatigue from a subordinate subscale to a primary/co-primary, comparable endpoint for research and quality governance [1].

Within standardized assessment windows, we recommend parallel capture of patient-reported outcomes-PROMIS-Fatigue (T-scores) and QoR-15-alongside digital phenotypes (steps/activity intensity, nocturnal sleep efficiency/arousal index, and heart-rate variability where feasible). Prespecified analysis plans should report QoR-15 MCID-based interpretations [11-13] and interval estimates/effect sizes for PROMIS-Fatigue (with anchoring to the QoR-15 MCID when needed) to strengthen cross-study comparability [1,3-5,11-12].

AIFS adopts a biopsychosocial lens, improving external validity, and integrates digital phenotyping to generate continuous, person-level trajectories that interface naturally with patient-reported endpoints and study design [11,12]. Validation snapshot and visual mapping of exposures→pathways→phenotypes→endpoints are shown in Figure 1 (AIFS overview).

Figure 1:

AIFS overview-exposures → pathways → phenotypes → endpoints Panels: A) Perioperative exposures: induction/maintenance drugs, opioid-sparing strategies, temperature & circadian care, sedation, and regional techniques; B) Linked pathways: inflammation/metabolism, neural circuits/arousal, circadian/sleep, and mood/cognition; C) Fatigue phenotypes/trajectories across standardized windows: Baseline ≤ 7 days; POD 1/3/7/30; POD 90 (optional); D) Endpoints & readouts: PROMIS-Fatigue (T-scores; higher = worse), QoR-15 (MCID ≈ 6 points), and digital phenotypes-steps/activity intensity; nocturnal sleep efficiency (SEI) / arousal index (AI); heart-rate variability (HRV: RMSSD/HF).

How to read: Arrows encode hypothesized directions from exposure → pathway → phenotype. Dashed lines denote context-dependent or indirect links (e.g., antiemesis/opioid-sparing mitigating fatigue via reduced nausea/sedation). Shaded bars indicate recommended sampling windows. “Dual-track” reporting means presenting i) mean differences with 95% CIs (and time × group where applicable) and ii) responder analyses using Δ QoR-15 ≥ MCID.

Abbreviations: AIFS: Anesthesia-Induced Fatigue Spectrum; PROMIS: Fatigue, Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System-Fatigue; QoR-15: Quality of Recovery-15; MCID: Minimal Clinically Important Difference; SEI: Sleep Efficiency; AI, Arousal Index; HRV: Heart-Rate Variability; RMSSD: Root-Mean-Square of Successive Differences; HF: High-Frequency Band

Four Axes of AIFS

The AIFS organizes modifiable perioperative leverage points into four axes-inflammation/metabolism, neural circuits/arousal, circadian/sleep, and mood/cognition-each linking mechanisms to clinical phenotypes and measurable indicators for stratification and decision-making.

1) Inflammation/metabolism. Perioperative inflammatory signalling can reach the brain via humoral immune-to-brain routes, triggering microglial activation and sickness-behaviour-like features (sleepiness, reduced motivation, heightened fatigue) that align with the clinical fatigue phenotype [6].

2) Neural circuits/arousal. Altered tryptophan-kynurenine activity-including shifts in the kynurenic acid (KYNA)/quinolinic acid (QUIN) ratio-relates to effort-reward appraisal and the subjective experience of fatigue [7]. Rising adenosine under wake pressure modulates cortical excitability via A1/A2A receptors, shaping the arousal-fatigue balance [8].

3) Circadian/sleep. Perioperative sleep/circadian disruption often amplifies fatigue phenotypes. A recent meta-analysis indicates that melatonin provides limited overall benefit for subjective postoperative sleep; therefore, routine use is not supported [10].

4) Mood/cognition & the inflammatory reflex. The cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway suggests that vagus-mediated cholinergic signalling can restrain peripheral inflammation and potentially lessen central inflammatory load; however, human evidence remains mixed, warranting higher-quality randomized trials [9].

The four axes guide stratification and strategy mapping-e.g., anti-inflammatory/metabolic modulation, sedation/opioid stewardship, circadian-friendly care, and mood screening/communication-and are integrated with digital phenotyping to enable continuous trajectory monitoring and treatment-response evaluation [11].

Quantification and Time Window of AIFS

Subjective outcomes

Use PROMIS-Fatigue (T-scores) as the primary axis for fatigue and QoR-15 for global recovery/comfort; parallel use reduces single-endpoint bias and facilitates cross-procedure, multicentre comparability [1,3,4]. The QoR-15 MCID is ~6 points (close to earlier ~8-point estimates) and supports between-group interpretation and responder analyses [13]. For PROMIS-Fatigue, report point estimates with SE/95% CIs at each time point and model time × group interactions in a repeated-measures framework; avoid a single universal MCID to prevent over-generalization across populations and settings [3].

Objective outcomes (digital phenotypes)

During hospitalization and after discharge, monitor steps/activity intensity and nocturnal sleep efficiency/arousal index; include HRV (e.g., RMSSD/HF) when feasible to complement autonomic recovery [11,14]. A large cohort shows greater early activity is associated with fewer complications and shorter stay [5]. Reviews emphasize feasibility and comparability with standardized sampling windows and clear pipelines; however, device/algorithm heterogeneity argues against universal thresholds, so prespecified interpretation rules and sensitivity analyses are needed [11,14].

In routine care, feasibility is additionally constrained by adherence and budget/IT considerations; we therefore recommend explicit completeness targets (e.g., daily wear-time; ≥ 70% days captured) and site-tailored procurement/pipelines, rather than cross-device “target lines” [11,14].

Windows and reporting

Use standardized windows-baseline ≤ 7 days pre-op; POD 1/3/7/30 [1]; optional POD 90-with parallel capture of PROMIS-Fatigue (T-scores) and QoR-15, plus objective metrics (steps/activity intensity, nocturnal sleep efficiency/arousal index; HRV [RMSSD/HF] when feasible). Report on two tracks: a) mean differences (time × group where applicable) with 95% CIs; b) responder analyses using QoR-15 Δ ≥ MCID (~6 points) with interval estimates [1,13]. For PROMIS-Fatigue, prioritize interval estimates/effect sizes and, when helpful, anchor interpretation to the QoR-15 MCID [3,13].

These windows align with recovery-trajectory evidence that patient-reported outcomes and sensor-derived activity/sleep metrics can be asynchronous over 1-3 months, improving comparability across studies [14].

Antiemesis and Opioid Management in the AIFS Framework: Breaking the Nausea-Bed Rest-Fatigue-Anxiety Chain

Prevention first, risk-stratified

Use Apfel risk stratification to guide multimodal prophylaxis in moderate-to-high-risk patients-e.g., a 5-HT₃ antagonist + dexamethasone, with dopamine-receptor or NK₁ antagonists added as needed-and predefine rescue pathways using a different mechanistic class than the prophylactic regimen [15]. This approach reduces PONV and lowers rescue use, thereby interrupting the cascade “nausea → limited intake → prolonged bed rest” [15]. Where feasible, opioid-sparing strategies can further diminish emetogenic load and support these pathways [16].

Opioid-sparing-avoid one-size-fits-all

Meta-analyses indicate that OFA/OSA is associated with lower PONV, whereas effects on postoperative pain and total opioid consumption are inconsistent across procedures; protocols including dexmedetomidine show bradycardia signals, so individualized selection and close monitoring are warranted [16,17]. For regimen refinement, systematic/meta-analytic evidence suggests palonosetron + dexamethasone can outperform common comparators in certain procedures/time windows, though heterogeneity persists and local pathways/drug access should guide formularies [18]. Additional RCTs at high-risk indications show benefit: pre-operative oral olanzapine added to dexamethasone + ondansetron reduced 24-h PONV in high-risk day-surgery patients (Apfel ≥ 3) [19]; in bariatric surgery, metoclopramide + ondansetron reduced PONV and decreased rescue use versus 5-HT₃ monotherapy [20].

Formal cost-effectiveness analyses (e.g., palonosetron + dexamethasone vs. generics) are outside the scope of this methods-first Part 1; selection should consider local pricing/licensing and pathway constraints.

Postoperative follow-up and feedback

Sampling windows and parallel reporting follow §4.(3). At the ward level, feed process streams (PONV events/rescues, opioid exposure, sleep metrics) to dashboards/early-warning workflows, applying the completeness/false-alert/workflow safeguards outlined in §9(2) to avoid redundancy here [1,3,4,5,12,13].

The "First-Night" Window of Dexmedetomidine and an Overview of Melatonin Research

First-night features and dexmedetomidine

The first postoperative night is typically marked by fragmented sleep and increased arousals, which tracks with next-day recovery. Across RCT meta-analyses, dexmedetomidine is associated with higher sleep efficiency (SEI), lower arousal index (AI), shorter N1, and longer N2; however, between-study heterogeneity is notable and bradycardia/hypotension require vigilance [21,22]. A postoperative intranasal RCT after joint arthroplasty improved LSEQ and actigraphy outcomes without excess adverse events [23]. In older patients with prominent sleep issues, low-dose, individualized strategies with monitoring are prudent [21-23].

Because first-night sleep endpoints are continuous (SEI/AI/stage proportions) and device-dependent, we summarize effects as estimates with 95% CIs; threshold-based NNT awaits harmonized responder definitions and dose/route-stratified datasets. For bradycardia/hypotension, we report absolute event rates with CIs when available, noting heterogeneity across dose, route, and procedure that currently precludes a robust pooled NNH.

Melatonin: mixed findings-no routine use

A recent systematic review/meta-analysis shows limited overall benefit of melatonin on subjective postoperative sleep quality; therefore, routine use is not supported [10]. Subgroup explorations (age, baseline insomnia/sleep disturbance, procedure type, and dose/timing) remain heterogeneous and largely low-certainty, with no consistent, clinically meaningful benefit across trials [10].

Given small/uncertain overall effects and the lack of consensus responder thresholds for subjective sleep, we report estimate-with-CI summaries rather than NNT. In practice, routine use is not advocated; for patients with pronounced preoperative insomnia or circadian disruption, a cautious, time-limited trial may be considered within local pathways, with sleep-focused outcomes and safety monitoring [10].

Implementation within AIFS

Sampling windows and reporting follow §4.(3). For patients troubled by first-night fragmentation, consider low-dose, individualized dexmedetomidine with monitoring to improve SEI and reduce arousals, recognizing evidence heterogeneity and bradycardia/hypotension signals; routine melatonin use is not supported given mixed evidence [1,3,4,13,14].

Technical Pathways of AIFS and Early Context-Dependent Effects

Across maintenance strategies, effects on early patient-centred recovery and fatigue are generally small to moderate and are shaped by procedure type, patient factors, and concurrent perioperative care (antiemesis, opioid-sparing, circadian and temperature management). Where quantified in recent syntheses, TIVA vs. volatile differences on QoR-15 typically fall within ≈1 MCID (~6 points) at 24-48 h and attenuate by ~72 h; opioid-free/-sparing reduces PONV with heterogeneous effects on pain/opioid use; dexmedetomidine yields small-moderate SEI/AI improvements with bradycardia/hypotension signals.

In older adults with hip-fracture surgery, the multicentre REGAIN randomized trial showed that spinal anesthesia was not superior to general anesthesia for the composite of death or inability to walk at 60 days [23,24]. For early patient-reported outcomes, an elective transsphenoidal neurosurgery RCT using QoR-15 as the primary endpoint found no between-group difference between propofol-based TIVA and sevoflurane; the difference was below the updated MCID, while emergence agitation and antiemetic rescue in PACU were lower with TIVA [13,25].

Given cross-trial heterogeneity in procedures, windows, and endpoints, we do not pool by procedure or provide a forest plot; instead we interpret early TIVA effects against the QoR-15 MCID and cite procedure-specific exemplars [14,25,26].

Within AIFS, sampling and reporting follow §4.(3); we emphasize how context (procedure, patient factors, antiemesis/opioid-sparing, circadian and temperature management) shapes fatigue trajectories (Figure 2) [1,3-5,12,15]. Ward-facing implementation and axis-intervention mapping are summarized in Figure 2; a validation snapshot-AIFS vs. ERAS vs. QoR/StEP-appears in Figure 3 to situate AIFS alongside existing frameworks.

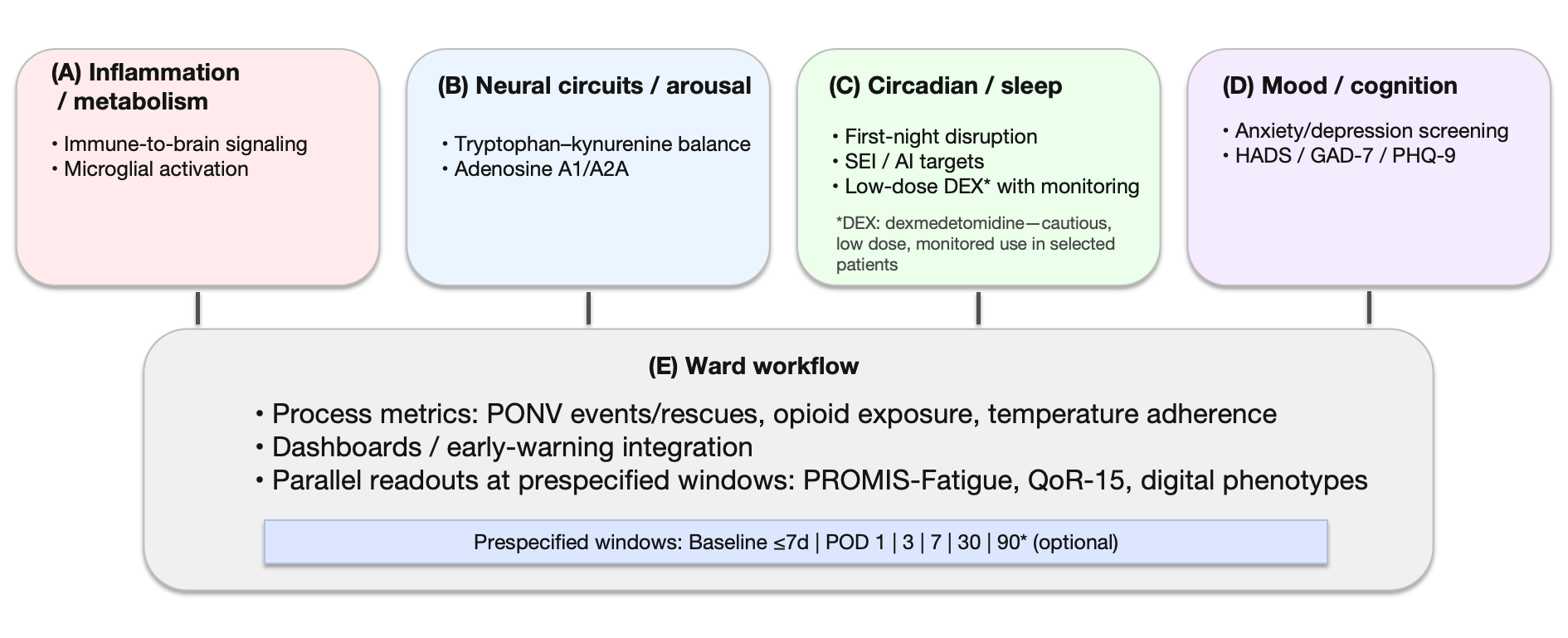

Figure 2:

The four-axis framework and ward implementation pathway

Panels: A) Inflammation/metabolism: immune-to-brain signaling and microglial activation as mechanistic conduits for postoperative fatigue; B) Neural circuits/arousal: tryptophan–kynurenine balance (e.g., KYNA/QUIN) and adenosine A1/A2A modulation of cortical excitability; C) Circadian/sleep: first-night disruption; operational targets include nocturnal sleep efficiency (SEI) and arousal index (AI); in selected patients, consider cautious, low-dose dexmedetomidine (DEX) with monitoring; D) Mood/cognition: anxiety/depression screening (HADS, GAD-7, PHQ-9) to identify cross-cutting “amplifier” effects; E) Ward workflow: process metrics (PONV events/rescues, opioid exposure, temperature-management adherence), dashboard/early-warning integration, and parallel readouts (PROMIS-Fatigue, QoR-15, digital phenotypes) at prespecified windows (Baseline ≤ 7 days pre-op; POD 1/3/7/30; optional POD 90).

How to read: Solid connectors denote core links between axes and clinical implementation; dotted connectors denote modulators/amplifiers (e.g., mood). Color blocks map representative interventions to each axis (antiemesis/opioid-sparing, circadian-friendly nursing, risk-aligned communication). The shaded bar indicates standardized assessment windows used for reporting and quality improvement.

Safety/implementation notes: Device/algorithm heterogeneity and adherence affect comparability of digital measures; use prespecified completeness rules, false-alert control, and role-based data entry. When DEX is used, monitor for bradycardia/hypotension and individualize dose/timing to patient and procedure context.

Abbreviations: AIFS: Anesthesia-Induced Fatigue Spectrum; AI: Arousal Index; DEX: Dexmedetomidine; GAD-7: Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7; HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; HF: High-Frequency Band; HRV: Heart-Rate Variability; KYNA/QUIN: Kynurenic/Quinolinic acid; MCID: Minimal Clinically Important Difference; PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionnaire-9; POD: Postoperative Day; PONV: Postoperative Nausea/Vomiting; PROMIS: Fatigue, Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Fatigue; QoR-15: Quality of Recovery-15; RMSSD: Root-Mean-Square Of Successive Differences; SEI: Sleep Efficiency

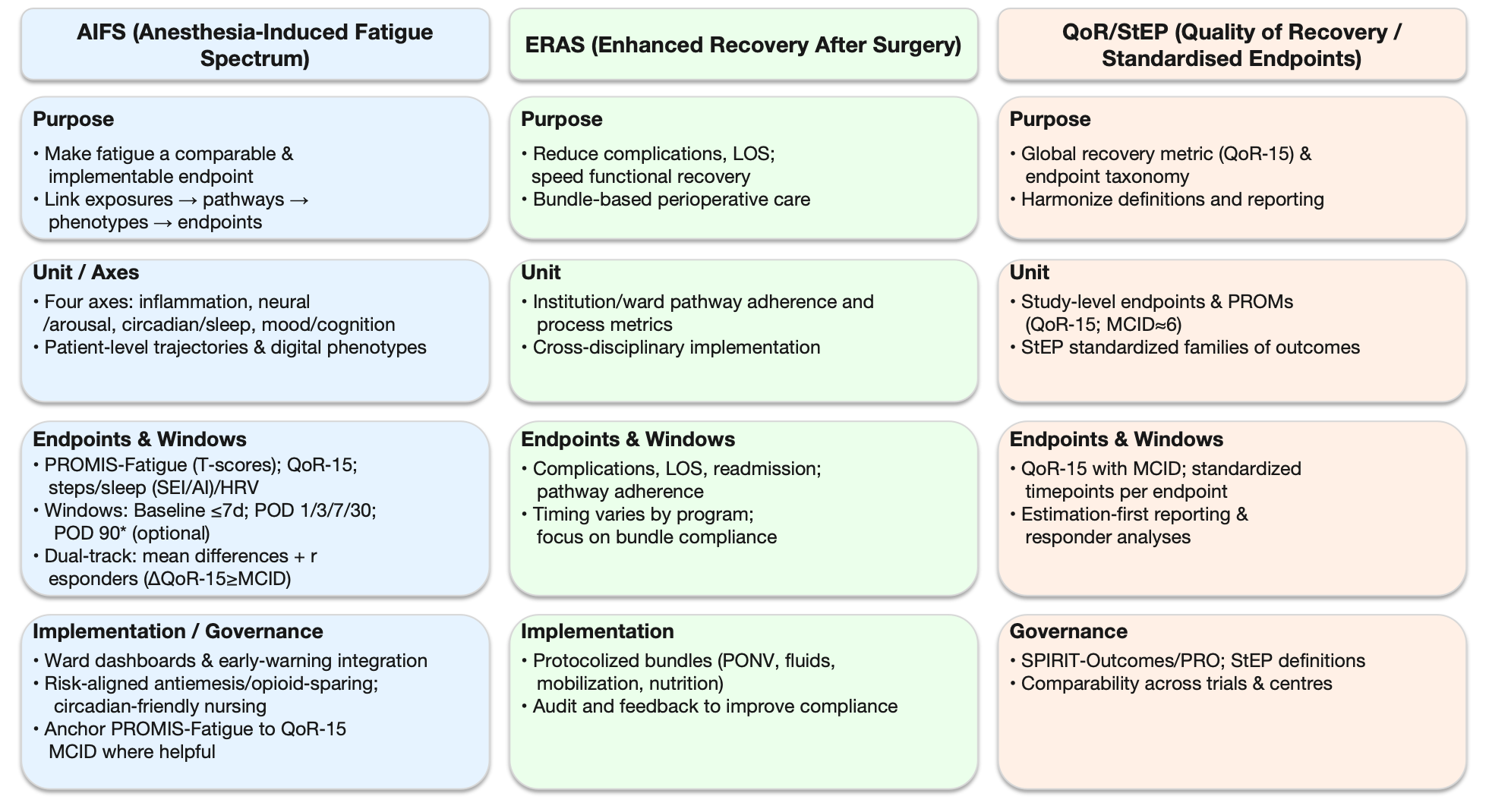

Figure 3:

AIFS vs. ERAS vs. QoR/StEP - at-a-glance comparison

What the figure shows. Three side-by-side panels summarize the scope and practical emphases of:

1) AIFS (Anesthesia-Induced Fatigue Spectrum): Makes fatigue a comparable, implementable endpoint by linking exposures → pathways → phenotypes → endpoints. Unit of analysis is the patient/trajectory. Readouts pair PROMIS-Fatigue (T-scores) and QoR-15 with digital phenotypes (steps, sleep SEI/AI, HRV). Windows: baseline ≤ 7 days; POD 1/3/7/30; POD 90 optional. Reporting: dual-track-mean differences with 95% CIs plus responder analyses using QoR-15 MCID ≈ 6 points.

2) ERAS (Enhanced Recovery after Surgery): Bundle-based perioperative care focused on reducing complications/LOS and accelerating function. Unit is the institution/ward pathway; key outputs are bundle adherence and process metrics (e.g., PONV, fluids, mobilization, nutrition).

3) QoR/StEP (Quality of Recovery/Standardised Endpoints in Perioperative Medicine): Provides the endpoint taxonomy and estimation-first reporting standards. Unit is the study endpoint; emphasizes QoR-15 with MCID and standardized time points per endpoint to support cross-trial comparability.

How to read: Rows align the frameworks by Purpose → Unit/Axes → Endpoints & Windows → Implementation/Governance. Use the AIFS column to operationalize patient-level trajectories; use ERAS for bundle design/audit; use QoR/StEP for standardized endpoint definitions and reporting.

Abbreviations: AIFS: Anesthesia-Induced Fatigue Spectrum; ERAS: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery; QoR-15: 15-item Quality of Recovery scale; StEP: Standardised Endpoints in Perioperative Medicine; PROMs: Patient-Reported Outcomes; MCID: Minimal Clinically Important Difference; LOS: Length of Stay; SEI: Sleep Efficiency; AI: Arousal Index; HRV: Heart-Rate Variability; POD: Postoperative Day

The Temporal Spectrum of AIFS: From Inflammatory Peaks to Functional Integration

Clinical windows of postoperative fatigue

Postoperative fatigue can be segmented into three windows: acute inflammatory (POD 0-3), metabolic remodeling (POD 4-14), and functional reintegration (POD 15-90). In the acute phase, inflammatory markers-particularly interleukin-6 (IL-6)-rise early and can aid detection of complications such as surgical-site infection (prospective spine-surgery data show strong discrimination at POD 3-7) [27]. During the metabolic window, an early-mobilization program achieved high targets (≥ 90% mobilized within 24 h; ~70-89% meeting POD 1-3 goals), supporting a bundled approach to activity-nutrition-analgesia [28]. These windows align with ERAS milestones: POD 0-3 maps to the early inflammatory surge, and POD 1-3 early mobilization signals transition into the POD 4-14 metabolic window, consistent with pathway synergy and real-world feasibility [2,28].

Asynchrony between PROs and objective activity

Patient-reported recovery and objective activity are not always synchronous: a multicentre study showed earlier improvements in PROs (e.g., KOOS JR, EQ-5D) and daily steps, whereas gait asymmetry and other sensor-derived metrics improved later, with different peak/valley timings over 1-3 months [29]. Within AIFS, we recommend standardized assessment windows (baseline ≤ 7 days pre-op; POD 1/3/7/30, optional POD 90) with parallel capture of PROMIS-Fatigue (T-scores) and QoR-15 alongside digital phenotypes (steps/activity intensity, nocturnal SEI / AI; HRV when feasible)-with modelling focused on baseline-normalized change, time × group interactions, and responder analyses as detailed in Sections 4 and 10 [3,14,30].

Digital Phenotyping in AIFS: Transforming “Feeling More Tired/Better” into Quantitative Trajectories

Digital phenotyping complements PROMs

Relying on patient-reported outcomes (PROMs) alone cannot capture recovery fluctuations and inter-individual variability; integrating digital phenotyping-continuous activity/sleep monitoring-adds time-resolved, objective evidence [11,30-32]. A multicentre study showed that earlier mobilization (accelerometer-measured) was associated with fewer complications and shorter stay, underscoring the process/warning value of activity trajectories [5]. Reviews indicate that with standardized sampling windows and explicit data pipelines, metrics such as steps/activity intensity and nocturnal sleep efficiency/arousal index are feasible and comparable, while device/algorithm/adherence heterogeneity argues against universal cut-offs, making prespecified interpretation rules and sensitivity analyses essential [11,30-32]; operational safeguards (completeness/false-alert control) are detailed in 9(2).

Operational use of ward-facing streams

Connect activity/sleep streams to early-warning systems or team dashboards to flag slow-recovery patients and trigger multidisciplinary actions, with prespecified completeness checks, false-alert control, and workflow mapping as core safeguards [31,32]. A lightweight cost/governance checklist (device/licensing, replacement/cleaning, data security, completeness monitoring, nursing workload) and a 4-8-week pilot should be used to calibrate alert rates and data capture before scale-up [31,32].

Within AIFS

Use standardized windows-baseline ≤ 7 days pre-op; POD 1/3/7/30, optional POD 90-to collect PROMIS-Fatigue (T-scores) and QoR-15 in parallel with objective metrics (steps/activity intensity, nocturnal SEI / AI; HRV when feasible) [1,3,30]. Report baseline-normalized change, time × group interactions, and trajectory phenotypes; when appropriate, conduct responder analyses using the QoR-15 MCID (~6 points) and anchor interpretation of PROMIS-Fatigue to this clinical threshold rather than imposing cross-device “target lines” [3,13,30]; detailed modelling and reporting conventions are summarized in Section 10.

Endpoint Governance and Reporting in AIFS: Making “Comparable, Interpretable, and Reusable” the Norm

Preregistration and endpoint hierarchy

Register trials and write protocols in line with StEP and SPIRIT-Outcomes/SPIRIT-PRO to predefine the endpoint hierarchy, the standardized assessment windows, and prespecified analyses-rather than treating fatigue merely as a subdomain of global recovery scales [1,33,34]. Protocols should pre-plan missing-data handling (e.g., mixed models with maximum likelihood; multiple imputation under plausible mechanisms) and adjust for key covariates (pain, sleep, mood) [1,33,34]. Collect PROMIS-Fatigue (T-scores) and QoR-15 in parallel at these time points, report interval estimates/effect sizes, and-when helpful for clinical readability-add responder analyses anchored to the QoR-15 MCID (~6 points) [1,13,33,34].

Using the QoR-15 MCID

The updated QoR-15 MCID is ≈6 points (earlier estimates ~8, similar magnitude), supporting a two-track readout: a) between-group Δ QoR-15 with 95% CIs and b) responder analyses using Δ ≥ MCID, reported as absolute differences with 95% CIs [13,33,35]. Because MCID is context-dependent (baseline distributions, scoring, populations), plan sensitivity analyses across 6-10 points or report multi-threshold bands to test robustness [35,36].

Reporting PROMIS-Fatigue

Because PROMIS uses T-scores (mean 50, SD 10; higher = worse), report i) point estimates with SE/95% CIs at each time point, ii) baseline-normalized changes (Δ from pre-op) with 95% CIs, and iii) model-based effect sizes (e.g., estimated mean differences/standardized contrasts), analyzing time×group interactions in repeated-measures models with prespecified missing-data handling [3]. Do not declare a single universal MCID; triangulate anchor-based (e.g., PGI or anchoring to QoR-15/MCID-see 10(2)) and distribution-based (e.g., 0.3-0.5 SD, SEM) approaches, and present plausible-band sensitivity analyses. If responder categories are explored, label them exploratory and report absolute differences with 95% CIs [3,36,13].

Parallel process and safety metrics

To reduce single-endpoint bias, co-report process/safety metrics-PONV events and rescues, total opioid exposure, temperature-management adherence-in the same windows as PROMIS-Fatigue and QoR-15, linking pathway → phenotype → endpoint and improving reusability across sites [1,33,34]. Use a reusable report template that includes the elements outlined in 10(1) (windows, endpoint hierarchy, models/covariates, missing-data handling) plus MCID interpretation per 10(2), sensitivity/subgroup plans, and site-specific governance. Privacy, security, and equity safeguards should be pre-specified (data-minimization, role-based access, encryption/patching/audit logs, incident response; loaner devices/non-wearable alternatives, multilingual consent, opt-out) with retention periods and responsibilities defined.

Bedside Workflow: The AIFS “Three-Step Loop”

Induction/Maintenance-reduce upstream fatigue-provoking load

Risk-stratified antiemesis: Use Apfel risk stratification to implement multimodal prophylaxis (a 5-HT₃ antagonist plus dexamethasone; add a dopamine- or NK₁-receptor antagonist when indicated), and pre-plan rescue with a different mechanistic class to blunt downstream effects of PONV on intake, mobility, and sleep [15]. In high-risk contexts, combine prophylaxis with predefined rescue and ensure hemodynamic monitoring when sedative adjuncts are used [15-17,21-23].

Opioid-sparing (avoid one-size-fits-all): Embed opioid-sparing within multimodal analgesia. Systematic reviews indicate that OFA/OSA generally reduce PONV, but effects on postoperative pain intensity and total opioid consumption show marked between-procedure heterogeneity; protocols that include dexmedetomidine carry a bradycardia signal-individualize selection and monitor closely [16,17].

First-night sleep disruption: For patients with pronounced first-night sleep fragmentation, consider low-dose, individualized dexmedetomidine under monitoring. Meta-analyses show higher sleep efficiency and fewer arousals, but between-study heterogeneity is substantial and hypotension/bradycardia remain safety concerns; geriatric RCT data suggest context- and patient-dependent effects [21-23].

Emergence and the first 72 h-symptom control in parallel with mobilization

Prioritize early oral intake, early ambulation, and nighttime noise/light reduction; deliver timely rescue antiemetics and minimize opioid exposure within multimodal analgesia to break the “nausea → sedation → bedrest” cascade [2,15]. When using OFA/OSA, emphasize individualization (procedure, risk, frailty) and dynamic monitoring (sedation level, hemodynamics, rescue needs) rather than a rigid pursuit of “zero-opioid” [12,16,17].

Postoperative follow-up & feedback-turn perceptions into trajectories

Within AIFS standardized windows (baseline ≤ 7 days pre-op; POD 1/3/7/30; optional POD 90) [1], display on a ward dashboard the subjective axes (PROMIS-Fatigue T-scores and QoR-15) in parallel with the objective axes (steps/activity intensity, nocturnal sleep efficiency/arousal index; add HRV such as RMSSD/HF when feasible) [3,30]. Report baseline-normalized change, time × group interactions, and trajectory phenotypes; for clinical interpretability, provide responder analyses using the QoR-15 MCID (~6 points) with 95% confidence intervals [13]. When interfacing wearables with dashboards or early-warning systems, pre-specify thresholds for completeness monitoring, false-alert mitigation, and nursing-workflow integration to reduce alarm fatigue and improve implementability [31,32].

Nurse-facing checklist & EHR hooks

We include a one-page nurse checklist (Appendix A) aligned to the AIFS windows and the “three-step loop.” It captures: i) antiemesis-prophylaxis class(es), rescue given (different mechanism), and PONV events (0-24 h/24-48 h/48-72 h); ii) opioid stewardship-24-h MME and non-opioid adjuncts used; iii) mobilization-out-of-bed/ambulation and target attainment (POD 0/1/2/3); iv) sleep/circadian-quiet-hours/lighting/temperature adherence and, when a ward wearable is available, overnight awakenings or SEI/AI; v) patient-reported snapshots-PROMIS-Fatigue (brief form where applicable) and QoR-15 at prespecified windows (Appendix A).

EHR integration mockup

We provide a simple field map (Appendix B) listing the corresponding EHR data elements: check boxes (e.g., “rescue antiemetic class ≠ prophylaxis”), numerics (24-h MME; steps or mobility tier), and scores (PROMIS-Fatigue T-score; QoR-15). Recommended implementation uses role-based entry, data-minimization, and on-device/edge encryption for wearable streams. Dashboards display parallel readouts (PROMIS-Fatigue, QoR-15, steps/mobility tier, overnight awakenings/SEI) in the AIFS windows (baseline ≤ 7 days pre-op; POD 1/3/7/30; optional POD 90) (Appendix B).

Emotional Burden within the AIFS Framework: A cross-cutting “amplifier”

Emotional burden is tightly linked to postoperative experience. Recent evidence shows that preoperative anxiety/depression is associated with higher anesthetic/analgesic requirements, worse patient-reported recovery, and-context-dependently-more intense postoperative pain; it may also be associated with altered pain trajectories and an increased risk of chronic postsurgical pain (CPSP) [37,38]. Mechanistically and clinically, anxiety, pain, and sleep are coupled; emotional burden likely functions as a cross-cutting amplifier across the four AIFS axes, indirectly worsening fatigue via pain intensification and sleep disruption. A cautious interpretation is association/amplification rather than a blanket causal claim [38-41].

Randomized evidence indicates that brief preoperative mindfulness-based interventions can lower perioperative anxiety and improve early patient-reported recovery without safety concerns, supporting a “screen → educate → targeted intervention” step in the AIFS pathway [41].

Implementation

- Screen & re-assess. Establish baseline with HADS, GAD-7, and PHQ-9 preoperatively, and re-assess at POD 7 and POD 30 to map the emotion-pain-fatigue nexus; consider procedure-specific tools (e.g., SAQ/PAS-7).

- Statistical handling. Pre-specify emotion measures as covariates/mediators/moderators and, when appropriate, conduct registered mediation/moderation analyses [40].

- Communication & interventions. Use findings to guide shared decision-making and trigger risk-aligned non-pharmacologic/pharmacologic strategies; align actions with pathway timing and escalation rules [39,40]. For screen-positive or high-risk patients, offer a brief preoperative mindfulness program (e.g., guided audio/app-based), referencing the RCT evidence [41].

- Within the standardized windows (baseline ≤ 7 days pre-op; POD 1/3/7/30; optional POD 90) [1], co-report PROMIS-Fatigue (T-scores) and QoR-15 in parallel with objective sleep/activity metrics, present interval estimates/effect sizes, and-when appropriate-add responder analyses using the QoR-15 MCID (~6 points) [3,13,30,38].

Conclusions

AIFS links exposures → pathways → phenotypes → endpoint governance, positioning fatigue as a first-class, comparable perioperative outcome; implement with standardized windows and parallel PROMIS-Fatigue/QoR-15 + objective metrics, analyzed under preregistered plans to ensure external comparability [1,3,30,33-36].

Practice synthesis: Combine risk-stratified antiemesis + opioid-sparing + circadian-friendly nursing; in selected patients consider low-dose dexmedetomidine with monitoring for first-night sleep (benefit signals vs. bradycardia/hypotension; heterogeneous evidence) [2,15-17,21-23]; feed process/recovery streams into dashboards/early-warning and interpret changes with QoR-15 MCID ≈6 for clinical readability [13,31,32].

Future work: Elevate fatigue to primary/co-primary, embed mediation/moderation, and align registration, reporting, and analysis with StEP, SPIRIT-Outcomes/SPIRIT-PRO, SISAQOL-IMI to facilitate reuse and scale-out of Part 2 tools/indicators [1,13,33-36].

Funding

National Natural Science Foundation of China (Project Approval Number: 81200858); Jiangsu Province 333 High-level Talent Training Project [Certificate No.: (2022) No. 3-10-007].

Clinical Trials from Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital, Affiliated Hospital of Medical School, Nanjing University, the Huai'an Matching Assistance Special Project (2024-2025.

Conflict of Interest

None.

AI Assisted Declaration

The authors used generative AI tools (e.g., ChatGPT, OpenAI) to assist in language polishing and formatting. All intellectual content, analyses, and conclusions are solely those of the authors.”

Presentation

None Declared.

References

- Myles PS, Wallace S, Boney O, Tramer MR, Wu CL, et al. (2025) An updated systematic review and consensus definitions for standardised endpoints in perioperative medicine: Patient comfort and pain relief. Br J Anaesth 134: 1450-1459.

- Ljungqvist O, de Boer HD, Balfour A, Fawcett WJ, Lobo DN, et al. (2021) Opportunities and challenges for the next phase of Enhanced Recovery After Surgery: A Review. JAMA Surg 156: 775-784.

- PROMIS (2023) Fatigue-User Manual & Scoring Instructions. Version: 2023, Chicago, IL.

- Bescond VL, Petit-Phan J, Campfort M, Nicolleau C, Conté M, et al. (2024) Validation of the postoperative QoR-15 score after emergency surgery. Eur J Anaesthesiol 41: 518-526.

- Turan A, Khanna AK, Brooker J, Saha AK, Clark CJ, et al. (2023) Association between mobilization and composite postoperative complications following major elective surgery. JAMA Surg 158: 825-830.

- Gao C, Jiang J, Tan Y, Chen S (2023) Microglia in neurodegenerative diseases: Mechanism and potential therapeutic targets. Signal Transduct Target Ther 8: 359.

- HE, SA M, A S (2024) Understanding the kynurenine pathway: A narrative review. Front Mol Neurosci 17: 1369798.

- Huang L, Zhu W, Li N, Zhang B, Dai W, et al. (2024) Functions and mechanisms of adenosine and its receptors in sleep regulation. Sleep Med 115: 210-217.

- Alen NV (2022) The cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway in humans: State-of-the-art review and future directions. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 136: 104622.

- Tsukinaga A, Mihara T, Takeshima T, Tomita M, Goto T (2023) Effects of melatonin on postoperative sleep quality: A systematic review meta-analysis, and trial sequential analysis. Can J Anaesth 70: 901-914.

- Solsky I, Haynes AB (2024) Beyond the physical: Digital phenotyping and the complexity of surgical recovery. Surgery 176: 519-520.

- Lirk P, Schreiber KL (2024) Lessons learnt in evidence-based perioperative pain medicine: changing the focus from the medication and procedure to the patient. Reg Anesth Pain Med 49: 688-691.

- Myles PS, Myles DB (2021) An updated minimal clinically important difference for the QoR-15 scale. Anesthesiology 135: 934-935.

- Wells CI, Xu W, Penfold JA, Keane C, Gharibans AA, et al. (2022) Wearable devices to monitor recovery after abdominal surgery: Scoping review. BJS Open 6: zrac031.

- Gan TJ, Belani KG, Bergese S, Chung F, Diemunsch P, et al. (2020) Fourth consensus guidelines for the management of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesth Analg 131: 411-448.

- Feenstra ML, Jansen S, Eshuis WJ, van Berge Henegouwen MI, Hollmann MW, et al. (2023) Opioid-free anesthesia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Anesth 90: 111215.

- Zhang Z, Li C, Xu L, Sun X, Lin X, et al. (2024) Effect of opioid-free anesthesia on postoperative nausea and vomiting after gynecological surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Pharmacol 14: 1330250.

- Kumar J, Alagarsamy R, Lal B, Rai AJ, Joshi R, et al. (2024) Comparison of efficacy and safety between palonosetron and ondansetron to prevent postoperative nausea and vomiting in patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Minim Invasive Surg 27: 202-216.

- Grigio TR, Timmerman H, Martins JVB, Slullitel A, Wolff AP, et al. (2023) Olanzapine as an add-on, pre-operative anti-emetic for preventing postoperative nausea or vomiting: A randomized controlled trial. Anaesthesia 78: 1206-1214.

- Ebrahimian M, Mirhashemi S-H, Oshidari B, Zamani A, Shadidi-Asil R, et al. (2023) Effects of ondansetron, metoclopramide and granisetron on perioperative nausea and vomiting in patients undergone bariatric surgery: A randomized clinical trial. Surg Endosc 37: 4495-4504.

- Liu H, Wei H, Qian S, Liu J, Xu W, et al. (2023) Effects of dexmedetomidine on postoperative sleep quality: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Anesthesiol 23: 88.

- Wang L, Liang X-Q, Sun Y-X, Hua Z, Wang D-X (2024) Effect of perioperative dexmedetomidine on sleep quality in adult patients after noncardiac surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. PLoS One 19: e0314814.

- Wu J, Liu X, Ye C, Hu J, Ma D, et al. (2023) Intranasal dexmedetomidine improves postoperative sleep quality in older patients with chronic insomnia: A randomized double-blind controlled trial. Front Pharmacol 14: 1223746.

- Neuman MD, Feng R, Carson JL, Gaskins LJ, Dillane D, et al. (2021) Spinal anesthesia or general anesthesia for hip surgery in older adults. N Engl J Med 385: 2025-2035.

- Feng Y, Zhang Y, Lian W, Xue Y, Ma M, et al. (2025) A randomized controlled trial to compare the effects of sevoflurane and propofol for maintenance of anesthesia on postoperative recovery quality in patients undergoing transsphenoidal resection of pituitary adenoma. BMC Anesthesiol 25: 392.

- YH, BR K, JJ L, et al. (2023) Propofol-based TIVA versus desflurane anesthesia for postoperative recovery in robot-assisted or laparoscopic nephrectomy: A randomized trial using the Korean version of QoR-15. Korean J Anesthesiol 76: 513-522.

- Roch PJ, Ecker C, Jäckle K, Meier M-P, Reinhold M, et al. (2024) Interleukin-6 as a critical inflammatory marker for early diagnosis of surgical site infection after spine surgery. Infection 52: 2269-2277.

- Jønsson LR, Foss NB, Orbæk J, Lauritsen ML, Sejrsen HN, et al. (2023) Early intensive mobilization after acute high-risk abdominal surgery: A nonrandomized prospective feasibility trial. Can J Surg 66: E236-E245.

- Christensen JC, Blackburn BE, Anderson LA, Gililland JM, Peters CL, et al. (2023) Recovery curve for patient-reported outcomes and objective physical activity after primary total knee arthroplasty-a multicenter study using wearable technology. J Arthroplasty 38: S94-S102.

- Lee J, Kong S, Shin S, Lee G, Kwan Kim H, et al. (2024) Wearable device-based intervention for promoting patient physical activity after lung cancer surgery: A nonrandomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open 7: e2434180.

- Bignami EG, Panizzi M, Bezzi F, Mion M, Bagnoli M, et al. (2024) Wearable devices as part of postoperative early warning score systems: A scoping review. J Clin Monit Comput 39: 233-244.

- Bellini V, Brambilla M, Bignami E (2024) Wearable devices for postoperative monitoring in surgical ward and the chain of liability. J Anesth Analg Crit Care 4: 19.

- Butcher NJ, Monsour A, Mew EJ, Chan A-W, Moher D, et al. (2022) Guidelines for reporting outcomes in trial protocols: The SPIRIT-Outcomes 2022 Extension. JAMA 328: 2345-2356.

- Calvert M, King M, Mercieca-Bebber R, Aiyegbusi O, Kyte D, et al. (2021) SPIRIT-PRO Extension explanation and elaboration: Guidelines for inclusion of patient-reported outcomes in protocols of clinical trials. BMJ Open 11: e045105.

- Pe M, Alanya A, Falk RS, Amdal CD, Bjordal K, et al. (2023) Setting International Standards in Analyzing Patient-Reported Outcomes and Quality of Life Endpoints in Cancer Clinical Trials-Innovative Medicines Initiative (SISAQOL-IMI): stakeholder views, objectives, and procedures. Lancet Oncol 24: e270-e283.

- Health Measures (2025) Meaningful Change for PROMIS®. Northwestern University, Evanston (IL).

- Shebl MA, Toraih E, Shebl M, Tolba AM, Ahmed P, et al. (2025) Preoperative anxiety and its impact on surgical outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Transl Sci 9: e33.

- Chen D, Yang H, Yang L, Tang Y, Zeng H, et al. (2024) Preoperative psychological symptoms and chronic postsurgical pain: Analysis of the prospective China Surgery and Anaesthesia Cohort study. Br J Anaesth 132: 359-371.

- Fernández-Castro M, Jiménez J-M, Martín-Gil B, Muñoz-Moreno M-F, Martín-Santos A-B, et al. (2022) The influence of preoperative anxiety on postoperative pain in patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Sci Rep 12: 16464.

- Alghamdi AA, Alghuthayr K, Alqahtani SSSMM, Alshahrani ZA, Asiri AM, et al. (2024) The translation and validation of the surgical anxiety questionnaire into the modern standard Arabic language: Results from classical test theory and item response theory analyses. 24: 694.

- Rajjoub R, Sammak SE, Rajjo T, Rajjoub NS, Hasan B, et al. (2024) Meditation for perioperative pain and anxiety: A systematic review. Brain Behav 14: e3640.